Welcome to the Lower Ouseburn Children’s Literature “Walk-Talk”.

Whilst we make our way along Lime Street under Byker Bridge perhaps you might like to try to come up with the five authors who won the most prestigious prizes, by writing about the north-east of England.

Did anyone come up with the 5 names.

In alphabetical order they are David Almond, Richard Armstrong, Aidan Chambers, Philip Turner and Robert Westall.

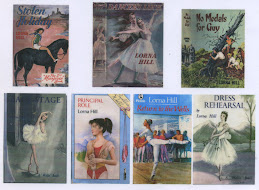

All male but, in fact, the author who used the Lower Ouseburn the most in her stories is female. Her name is Lorna Hill.

That's her photograph that you can see above. In the margin on the right you can see just some of the children's books that she wrote.In fact she wrote more children’s stories about the north-east than any other author.

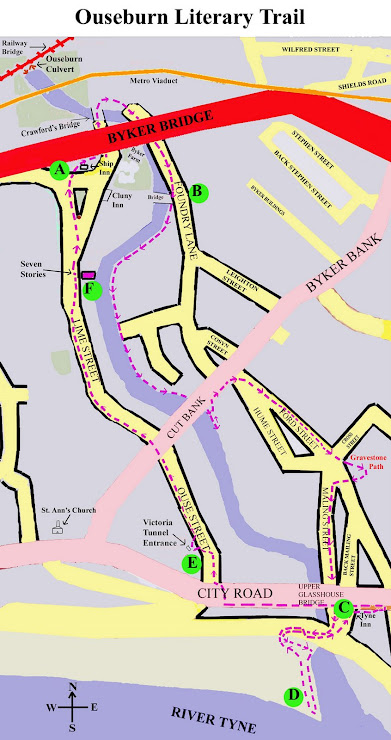

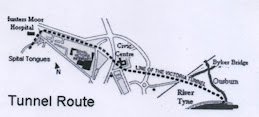

We’ll be visiting five main sites during this talk – A.B.C.D.E. and we will be mentioning the work of 4 Carnegie Medal winning authors and one Hans Andersen prize winner, whom we can, in various ways, associate with this little valley. By no means have all of them have written about this specific place but all the references are to northern stories and, though fictional settings are referred to, so many of their stories could have happened here.

Location A

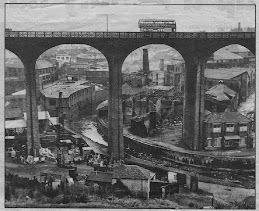

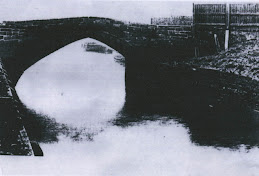

Look at picture of Byker Bridge in the margin to the right.

Byker Bridge is not really a bridge at all, but a viaduct. It connects the city of Newcastle with the industrial suburb of Byker on the east. From the parapet of the bridge itself, you could drop a stone upon the roof of No. 13 Brewery Terrace, where Sam lived with his foster parents.

This is from Chapter 3 of “The Secret” by Lorna Hill. Already the plot of the book is well underway and the words “foster parents” give you a clue that this last “Sadler’s Wells” book in the series of 14 is about the search for identity. It is a story of mixed-up babies. One, a little girl called Vanessa, ends up as the rich heiress on a country estate in Northumberland. The other, Sam, grows up under Byker Bridge. And Lorna Hill gives us a glimpse of what the area was like in the 1950s

Over Byker Bridge roars the heavy traffic of industrial Tyneside, while underneath it, stretching for miles, are the shining, glinting roofs of factories and warehouses, and away to the south, a glimpse of the murky River Tyne. The clank of machinery, the hoot of shipping, and the roar of the traffic overhead, composed the lullaby that hushed Sam to sleep at nights when he was a small baby.

Whatever his birth, the boy fits into this world like a hand into a glove and yet also rises above it.

Sam was a real Geordie …….and Sam was very proud of that fact. For the first ten years of his life, he spoke with a broad Tyneside accent, along with his playmates. He called people “man”, or “hinny”, regardless of their sex. The neighbours were “canny bodies” if you liked them, and “daft” if you didn’t. But gradually, under the influence of school, you would hardly have known he had been brought up under the arches of Byker Bridge.

Lorna Hill, with some artistic licence, tries to intensify the apparent squalor of the world beneath the bridge by inventing new details as well as combining them with some features that were certainly true.

There were not many houses left under Byker Bridge now – they had all been pulled down under the Slum Clearance Act, and factories and warehouses had taken their place. But Brewery Terrace was an exception. It, together with the Old Brewery, had apparently been forgotten. It may be said that Brewery Terrace lived up to its name, for the chimneys of the Old Brewery belched forth not only smoke but beer fumes as well – or so it seemed to Lady Waterford, when, during the first few years of Sam’s life, she called at No.13 to see how the adopted baby was getting on.

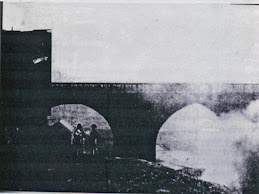

So, which was the model for Brewery Terrace ? One old photograph gives us an impression of the maze of streets and alley-ways where Vanessa is soon going to be running for her life. Another old photograph picks out the last surviving terraces that we saw on the first picture. Could you really drop a stone on to those roofs ?

One thing is for sure there is no record of there ever being a brewery. Other Lorna Hill characters in other books live for a while in the West End of Newcastle where the overwhelming beer fumes were an everyday feature of life.

The purpose of the book is to emphasise the different opportunities that opened up for Sam and Vanessa. They really are meant to be worlds apart and yet linked by a common destiny. However, whatever its shortcomings in material and aesthetic terms, Lorna Hill was keen to emphasise those qualities that made the place special.

the spirit of neighbourliness

the closely knit community.

everyone rallied round the Taylors.

Except the O’ Leary brothers !

Full use of this locale is used for the climax of the novel. Pulled by an instinct that almost overwhelms her, Vanessa makes her way to Brewery Terrace to find out the truth about their parents that she knows that Sam has uncovered. Fortunately for the reader, but unfortunately for the heroine, she has chosen a foggy day. She stands on Byker Bridge: Look at pictures alongside.

Looking down was like looking into a witch’s cauldron ! Clouds of evil-smelling vapour boiled and seethed in the dark abyss below her. It gave the impression of a bottomless pit, since all the lights of the warehouses and factories along the river bank were blotted out by the fog. Occasionally, out of the darkness, came the muffled wail of a ship’s siren, and sometimes, far away, the answering wail of a fog-horn out at sea. They were like two prehistoric monsters talking to one another, thought Vanessa ! Pervading the whole was the dull roar of traffic grinding along in bottom gear. Soon – though Vanessa didn’t know it – even that noise would stop, as the city’s traffic was brought to a complete standstill by “a real pea-souper”.

“Well, if Brewery Terrace is underneath the bridge,” reasoned Vanessa, “it’s not a bit of use my standing up here. I must get down there somehow.”

In one photo taken near the railway bridge it looks like the photographer tried to frame it to suggest the inside of a cauldron.

The writer takes us down there with Vanessa and develops the threat that awaits by several hints.

Then, as you expect, come the O’Learys and the chase through a warren of streets and warehouses that takes her on to a quay and .… into the water ! Can you guess what happens ? I’m not saying.

Before we move to our second venue let’s take a look upstream. Where does this water of the Ouseburn come from ?

Go for one mile over the top of the culvert and you will eventually come to Jesmond Dene and the parks surrounding it. The contrast between this grubby industrial landscape and the beauties of Jesmond Dene has been used by at least two children’s authors.

The best example again comes from Lorna Hill in her book “Swan Feather”. Peter and Sylvia experience one of the cold northern winters.

There was even ski-ing in the Cheviots, and skating on Paddy Freeman's Pond. was.. The two of them would skate until the moon rose and floated over the city like a great Chinese lantern.

Warning notices about thin ice have taken the place of skaters and local residents ensure that a small patch of water is kept open for the birds. However, you can still climb the eighty feet or so from the Ouseburn and gaze out at the moon hanging in the blue velvet sky over the Jesmond suburbs.

However, a feather is at the centre of the story,

She is called Sylvia Swan and so Peter gives her a feather. It’s her good-luck token. She loses it. She finds it again. It gets burned by the nasty villain of the story in a fit of temper.

The characters in “Marle” by Aidan Chambers have to decide whether to work on in the city or to return to their homes on Lindisfarne.

How appropriate that Jesmond Dene, portrayed as an oasis in the city, should be the place they choose to talk things over.

Susan was waiting when I arrived back in town.

"I've some sandwiches and some drink. Let's go to the Dene,' she said. Jesmond Dene is a woody park in the city. It was dappled with leaf-filtered sunlight, and we sat and ate the meal by the stream where it splashes down an outcrop of rocks. Ferns fanned up about the edges. Nearby a woman dandled a baby on her knee.

Just that one short scene but the image of the place caught immediately. The kaleidoscopic effect of the light through the trees and idea of the slow waving of the ferns conjures up immediately the particular visual sensations that can be experienced by the mill-house waterfall on any sunny summer’s day.

Location B

If the Dene, a haven of peace and tranquillity, is the obvious place to set scenes of love and romance, we should also stop to consider how ironic it is that nearly all of its attractions are the result of a gift to the city by Lord Armstrong, the great Tyneside armaments manufacturer. For our next stopping place on the walk is near Foundry Lane – a road name after the factory which formerly produced iron and steel.

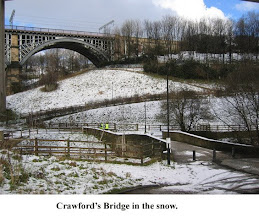

To continue the walk you must approach Crawford’s Bridge and turn to the right. Now follow the pathway back towards position B which is marked on the map at the top of the page.

We are now at Foundry Lane which was named after the iron and steel works which grew up on the spot. There’s nothing to see but this is where we must use our imaginations.

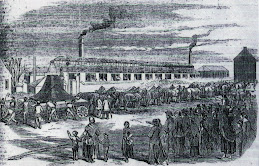

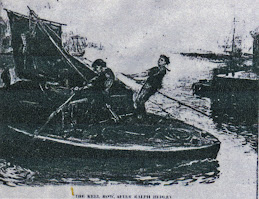

As you can see, we only have one rather dark and dingy photograph of what it used to be like. You have to stand on the bridge at Cut Bank Road. In the middle is the Ouseburn, on the left are the warehouses – some of which remain today. And on your right are the buildings of the factory. Outside the factory are the wherries with their cargoes of iron ore or coal.

Now consider approaching this site from the other direction as you do from under Byker Bridge.

What must it have been like to be a boy working in one of those foundries ? There is one place we can go for our answer.

And this brings us to the story of “Sabotage at the Forge” by Richard Armstrong. This is set in the fictional Valley Forge - a place very like the Ouseburn Foundry.

An old magazine illustration (The Illustrated London News) shows one of the products of this sort of foundry (a huge anvil) being got ready to be moved by a team of horses to Lord Armstrong’s factory in Elswick. It was a massive undertaking to get such a heavy load up roadways like Stepney Bank or the Cut Bank. Once at the top they had only just accomplished the first stage of their long journey across Newcastle to the massive factory complex upstream.

All around the area were foundries and other iron works on the fringes of a great city gradually changing from rural backwaters to the centres of heavy industry that finally overwhelmed the surrounding landscape. Such a place was the valley bottom of the Lower Ouseburn.

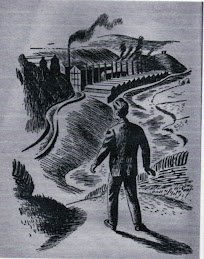

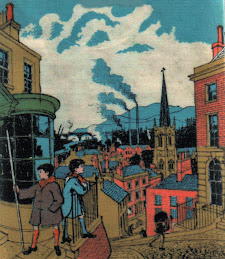

Here, for example, is a picture of how the illustrator (E.C.Lupton) saw the pleasant valley being dominated by the smoky factory on the Deneside.

It is quite easy to understand what an upheaval this must have created into people’s everyday lives. Much more difficult to take in is the way in which the local people reacted to this change. Strangest of all is the extraordinary feelings that began to develop both about the jobs they were doing and the materials they were working with. This is the emotional territory that our gifted author is able to explore in a way that is not matched by any other children’s author anywhere in the world. The adults in the book struggle to convey the feelings that they have.

Notice how Richard Armstrong puts these words into the mouth of old Jackie Rigby (who can neither read or write) to suggest the intensity of the experience of working with metal to the young apprentice who is the hero of the story. In these early scenes he is able to convey the horror of what may happen.

“Queer stuff. To you, it’s just steel. It’s hard and heavy; its blue and rough, or maybe shiny and smooth; but just steel. To me it’s more. It sort of lives, Thias, and I feel it like that, Maybe it’s the sweat that’s in it, and the power of the men that mined the ore and those that made it. Their strength and the skill of their hands. Maybe it’s that makes it queer. I don’t know, but sometimes it works sweet and easy, and other times it’s sort of sullen and you’ve got to fight and wrestle with it. And sometimes it’s even angry and you can’t do anything with it all. That’s when it maims men, Thias, and even kills them.”

This gives some impression power of the elements the men and boys are working with. Richard Armstrong reminds us of the heat, the noise and the constant smell of burning sulphur. There are also passages about how the once lovely valley has become a spoil heap of the awesome monster that is progress.

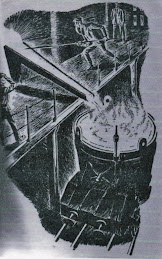

But “Sabotage at the Forge” is a story and not a description. There’s plenty of plot and characters to grip young readers. In fact there are two storylines – which are summed up by the next two pictures.

There he is – Bull Chadwick - and, yes, he is a bully. His sole objective in life is to torment the lives of the young boys who are working alongside him. Thias, the hero of the book spends a lot of his time trying to find a way of getting this tyrant to behave properly.

The second plot is somewhat different.

In the two hands is a bolt which has given way and ruined the biggest job the forge has ever handled. Only Thias knows that the bolt has been cut rather than snapped. Someone has carried out an act of deliberate sabotage. Thias is determined to find out who has done it.

His first suspicions fall on master forgeman, Jackie Rigby, who has just been forced to retire. But first suspicions often prove to be wrong. At the end of the book Thias has gained a new understanding of both his workmates and his job.

Thias was fascinated by it all. Because he wanted to make amends to Old Jackie for misjudging him, he gave everything that was in him to the work. That was in the beginning, but after the first few hours the job itself absorbed his strength and his thoughts, and towards the end of the week he was dreaming of it at night.

And when at last Saturday came and it was finished, more than a gun-tube had been forged. The vague feelings and half-understood ideas which had come to him that Sunday on the fell had sharpened and taken form.

He knew now what the fierce gleam he had seen in the eyes of both Old Jackie and Ted Arkle meant. He knew as he stood with old forgeman and Jim Varty, watching the yard engine haul the forging down the yard to the fitting shop. It was pride of achievement, and he knew because he had felt it himself.

“Sabotage at the Forge” is a book about our industrial heritage but it is also a very good children’s adventure story.

Richard Armstrong was the first ever North-East Children’s author to win the Carnegie Medal. This was for his story for boys called ‘Sea Change’. It tells the story of a young apprentice and his voyage from Liverpool to the West Indies and back. It is a story about a young man coming of age. You will find more echoes of Armstrong’s own story in section D of this walk. Like young Thias Armstrong himself went to work in a huge foundry. He started as a young labourer, became a greaser apprentice and then was promoted to the responsible job of crane driver. It was an early taste of how work could become the route to personal growth and achievement. At the end of the First World War young Richard made his own more drastic sea-change. He left his job in the factory and went away to sea. Again he made steady progress from being an ordinary deck-hand to the officer class and all the responsibilities that come with a higher rank as a radio operator.

The second stage of his career finished in the late 1930s when he left the sea and tried to find work ashore whilst he moved towards his destiny as a moving and compelling writer. It was another sea-change, making yet more demands on his personal resilience. He worked as a secretary and as an undertaker’s assistant whilst he learned yet a new craft. His early stories of young boys in the Tyne valley and then as an apprentice in a forge echoed the experiences of his childhood.

‘Sea Change’ was the break-through and led to further stories of the sea such as ‘Danger Rock’ (which won a famous New York literary prize). His north-eastern background was not forgotten in his story of the north-eastern pits called ‘The Whinstone Drift’ or his acclaimed biography of ‘Grace Darling’.

Realism is the key to his work. He never shirks the real world and the problems that face young people as they come to terms with their employment and their future.

A quiet walk alongside the Ouseburn behind the ‘Seven Stories’ building takes you past the inner moorings of the boat club and the haunts of the ducks and the swans.

Don’t forget to look back when we get to the Cut Bank bridge and see if you can visualise what we saw in the first old photograph. You can pass easily under the bridge and come out on the other side of the busy road.

Head up the hill and make your way to Ford Street. There in the long walls you can find many examples of the locally produced Jubilee Brick. Can you spot the ones that have been inserted upside down ?

At the end of Ford Street you will find the gravestone path. It was covered with snow on the last occasion I visited it and took the photograph. I brushed aside one small heap but it is difficult to see. Far better to choose a sunny day and look at the stones amongst the grass.

How long, I wonder, will this monument survive the ravages of the lawn-mowers that skim over its surface in the summer months ? It is surely worth some short time pausing to see the inscriptions recording the poorer people of Newcastle who were buried nearby. Many, we must also remember, were so poor that these transplanted gravestones would have been a luxury too expensive for their families to contemplate. There were many other unnamed victims consigned to the ballast hills plague pits.

Location C

Before we pass under the Glasshouse Bridge (Location C)and meet the Tyne, let us examine a small reference in Winifred Cawley’s “The Feast of the Serpent” which is set in the days of the English Civil War.

Look at Picture C1. Can anyone tell me what sort of bird we have here. Yes, you are right – it is a thrush.

From one trivial detail we can trace a gruesome and horrible story that is closely based on an incident that really happened. It is something which reflects no credit on the people of Newcastle, though the author of “The Feast of the Serpent”, Winifred Cawley, manages to find her own way of confirming the healing and uplifting power of love.

Adonell Heron is the child of a gypsy mother and a border reiver father. Her home is at Elsdon, right in the middle of raiding territory. When her father is taken and hanged at Carlisle Castle, Adonell’s mother rejoins the wandering gypsies people and is taught their special ways. After the death of her mother the young girl makes her way to Chirton, near North Shields, where a young man she knows called Archie Rede will look after her. From Chirton the scene moves to Newcastle and to the beginnings of a tragedy.

It is the time of the infamous witch trials when ridiculous superstitions hold sway amongst many ordinary people. To be brief Adonell is accused of liaison with the devil and cast into prison with another thirty three women. A witch-finder from Scotland conducts the interrogation in Newcastle Town Hall.

The first case to be heard is that of Kattren Welsh, a poor woman from the slums at the eastern end of the town. A young boy gives evidence that he had seen “a group of women dancing round a horned creature in an old fort” somewhere “in Shieldfield.” Then she is accused of having a witch’s familiar imp or demon in the form of a bird that will come when she calls.

Kattren protests that it is her tame thrush called “Killico” that “she found in the Ouseburn not far from Glasshouse Bridge”.

Old, ill-educated and intimidated by the Witchfinder accusing her, the miserable Kattren is unable to do more than protest her innocence. The ultimate “proof” of the guilt of all the women is established in a degrading and revolting trial by “pricking”. The females are searched for the mark of the devil and then they are jabbed with a needle to see if it will draw blood. As there was a fee of twenty shillings for all that were found guilty many witchfinders equipped themselves with retractable needles that would not penetrate the skin.

In Newcastle, in the real case, thirty women were brought before the court in this way and twenty seven were found guilty. Fourteen women and one man were executed on the Town Moor, not one of whom would ever admit their guilt. We have two illustrations of this grisly event in the picture you can see. (Further details of witches in Newcastle can be found in the Discovery Museum)

From this awful tale Winifred Cawley extracts her sign of hope. Adonell is saved, found innocent when all hope seems lost. Saved but humiliated, the poor girl has little left to live for - until Archie reaches out to claim her for his bride in front of all the people present in court.

A more harrowing scene is used to end the book, Archie and Adonell take a walk on to the town moor to visit the scaffold and see the more unfortunate victims of the ‘witch fever’. At the foot of one execution they find the proof they needed that all of them were entirely innocent. Most of the so-called witches were buried in St.Andrew’s Church in the city centre.

Before we cross the modern Lower Glasshouse Bridge take a look at the picture, which shows the seventeenth century structure before its demolition in about 1904.

We get another view of the bridge and the Tyne Inn from the riverside end in this artist’s impression. Let’s try to stand on the very spot from which the artist drew his picture.

Location D

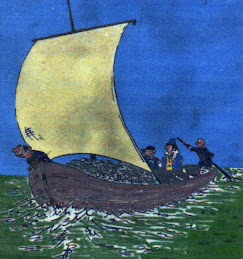

As you face the Tyne at the mouth of the Ouseburn (location D) to your right is the area formerly known as the North Shore, a part of the river bank regularly serviced by the famous keel-men. The picture shows us a keel man in his traditional uniform.

In “Down the Long Stairs”, also by Winifred Cawley, the young Ralph Cole, son of one of the famous hoast men, one of the traders who held exclusive rights over the coal trade on the Tyne, is making his journey down the river to meet his fate. As he passes beyond the quays we are given a glimpse of the open country still visible in the 1640s just outside the city walls.

At this moment Jackie was too busy with the keel to have time for much talk with me. He knew most of the watermen on the river and was hailed constantly from other keels as we made our way down the Tyne. From many of the colliers, too, a greeting was shouted to us across the water. It was turning into a lovely day, and after a while I found it hard to stop myself from enjoying the fresh breeze and the steady progress of our keel through the tall-masted ships, and past the pleasant green meadows and trees on both banks of the Tyne. The whole of this summer Emmet and I had been Cooped up indoors by the prolonged wet, and inside the city walls by the regulations of the Governor and by my mother's fears.

Little does Ralph know that his own foolishness and rash behaviour is going to fulfil all his mother’s worst fears. He has left home for ever.

A differing vision of the river appears in “Wildcat Tower” by G,Christopher Davies in 1877.

When trade is brisk the Tyne is a remarkable river. All the way down. Even as far as the sea, eight miles away, its banks are crowded with foundries, ship-yards, alkali works, and other noisome and noisy manufactories. The yellow surface of the river is covered with fussy, businesslike tugs, grimy-sailed colliers, huge iron steamers, and flat tub-like keels or barges, which float up and down with the tide, and sail wonderfully well with their small sails. The river runs in a deep ravine, and the evil smokes and smells which arise from its banks and from the vessels it bears, hang over it on quiet days in a very palpable cloud, and on windy days are dispersed over the neighbouring countryside until the vegetation suffers from the alkali, and the trees become stunted and bare, and present a most woeful appearance.

This ghastly vision comes from some 20 years before the author of the grim but somehow uplifting ‘Sabotage at the Forge’ (Richard Armstrong) was even born.

So what did a Keelboat really look like ? They had disappeared by the early 1830’s – just before photography could capture the definitive image. Look at the picture and you can see an artist’s impression. Look at the illustration from “Joe and the Magpie”, a modern cartoon adventure story for children. There was normally a captain, two mates and a boy – who was called a peedee. Imagine them there out on the river. Now imagine instead the raft that features in our most modern story – “Heaven Eyes” by David Almond.

"We passed the city's dark outskirts, the dilapidated quays: more ruined warehouses, broken wharves, massive billboards showing how this place would be- once the demolishing, building and developing started. Huge gaps of blackness where there was nothing.

The river stank of oil and something rotten. There was the scent of salt and seaweed. We passed the stream called the Ouseburn and hit more eddies where the currents of the stream and river mixed. Then the mist, thin at first, still allowing the moon and stars through to us.

"But it thickened, deepened. Soon there was nothing but us, the raft, the churning water and the mist."

In this part of the river, at least, the scenes of dereliction are mostly gone. The Black Middens that he envisages as just off the mouth of the Ouseburn do not exist. Robert Westall’s Black Middens, used so effectively in his Tynemouth tale, “The Watch-house” are near the mouth of the Tyne. It’s our imagination that must allow us to take the trip with Erin and January on the raft. If we glance across and peer down the river to Gateshead can we see the remains of Stoneygate and the territory of “Kit’s Wilderness” -another of David Almond’s local books.

Before we leave the modern quayside let us consider another book by Walbottle born Richard Armstrong. This is ‘Greenhorn’ about a young boy who sets sail from this place just as Armstrong himself did to a life in the merchant navy. Only a total beginner would ever turn up to his first ship in two taxis and thus become the object of scorn for his fellow apprentices.

It is a minor incident perhaps but starting off on the wrong foot and then spending your time recapturing the lost ground is one of the commonest experiences of youth. The young apprentice has to oversome not just his own awkwardness and inexperience but also the restrictive bonds imposed by an already settled team. How apt that his story should begin on the quayside. Thousands have begun their working life at this spot. A small cargo tramp is an unlikely vessel to send out into the world of literature. Yet Richard Armstrong made the journey and can take us all with him as we chart his many stories.

The 1965 Carnegie Medal winner Philip Turner claimed Canada as his place of birth. Critics have often believed that his 'Darnley Mills' stories were all set exclusively in Yorkshire. This clearly is mostly the case. However,when he was asked he commented that he had spent some of his early days in Newcastle and Leicesterhire. His fictional creation owed much to many places he had known including Yorkshire.

'Even so it is a Yorkshire which stretches to the Scottish border.'

The Newcastle reference intrigued me and I resolved to find out more. Turner's father was a clergyman who served for a time as the joint curate of Newcastle Cathedral. This put him on the spot for a literary connection with this city. But there is more ! And it is remarkably surprising. There were two joint curates of Newcastle Cathedral back in the late 1920s. One was Philip Turner's father and the other was Victor Hill. Victor Hill was Lorna Hill's husband. You will remember that Lorna Hill's photograph is near the top of this page. The events of 'The Secret' were largely based on Lorna's memories of her husband's mission in the Ouseburn in the late 1920s. It is not unreasonable to surmise that this small,poor area played a large part in the lives of both men and their families when Philip Turner was a young boy and Lorna was a new wife. Victor and Lorna moved to their parish in Matfen. Yet she never forgot those early days. Surely Turner's imagination and memory drew on this area (as well as the many others involving Yorkshire and the East Midlands).

Follow the marked trail on the map up past the Tyne inn and out on to the Glasshouse Bridge and City Road.

As the traffic roars by look down again at the bends of the river and remember that during World War 2 the German bombers used to follow the bends of the Tyne as they headed for Newcastle City Centre and the factories to the western side.

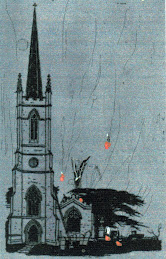

Also, about half-way across, I would like to stop briefly to indicate an important landmark. Please take care on the busy road. Look westward up the City Road to the outline of St.Ann’s Church. Cross the road carefully to Ouse Street and make your way to the entrance of the Victoria Tunnel. (Location E)

Location E

What happens when a war breaks out and bombs start falling on your part of town ?

During World War 2 both the Ouseburn Culvert and the Victoria Tunnel were used as air-raid shelters. The German bombers would fly up the Tyne and some would turn right up the valley in order to target the factories and the two great viaducts. When the all-clear sounded the little community would emerge to check on the vital ingredients of their world : their homes and those of friends and relations, the factory, the school and the local church.

We quote from the Dene Heritage magazine where Dora Nichols records her own memory of the Blitz.

I can remember the last war very well. All the houses along Gordon Road and Dibbly Street (near the top of Byker Bank) were hit, we thought the church had been hit but it hadn’t.

The house, the school and the church – together with the factory those are the pillars of the community that people turn to when danger threatens. St. Ann’s Church which we spotted from the Glasshouse Bridge came under attack and many of the houses around it were burnt to the ground.

Look at the photograph which was taken at Manors Depot, just along the road, at the height of an air raid.

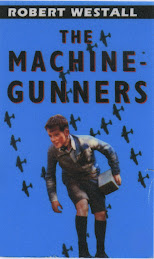

And once again we can turn to children’s writers to get some idea of what it must have been like to be there when the bombs fell. Double Carnegie Medal winner Robert Westall faced his trauma at the mouth of the Tyne but the feeling is surely the same. The horror, the confusion and the helplessness are all here in this extract from “The Machine-Gunners” where he emerges from a shelter just like this after the “all-clear” has sounded.

At the far end of the street the red brick spire of Holy Saviour's was burning. Flames licked from every window from top to bottom, joining into a smoke-column that blew away east. Even the Germans across the North Sea would be smelling the burning this morning. And laughing.

His father was asking a policeman which streets to the lower town were open. The policeman was shaking his head. Chas watched the church. God lived there. If even God wasn’t safe from Hitler, who was? Why didn't God get Hitler for what he was doing?

As he watched, the spire seemed to shimmer in the ~ It was shimmering more and more. It was twisting, like an outlaw shot in a Western - all that great brick height. It made Chas feel dizzy. Even a hundred yards away, he wanted to run. Great chunks of brickwork fell inwards into the church spire, like a jigsaw breaking up.

'I watched Holy Saviour's being built, as a kid.' said Mr McGill.

'Will they build it again?"

‘God knows.' But did God know?

Mr. McGill has lost a part of his childhood. Young Chas has been left with a memory that he will never forget. Robert Westall has ensured that it has become part of our heritage that will never be lost so long as there are stories to be told and people to read them.

Not every one disappeared underground into places like the Victoria Tunnel when the bombers came.

In his fictional North-East community of Darnley Mills another Carnegie Medal winner, Philip Turner, plunges us into similar trauma but as the seventeen year old characters in “Dunkirk Summer” face the same situation they invest us with a spirit of hope and resolution. Andy Birch, a sixth-former from London evacuated to Darnley Mills, has found himself gradually feeling at home in the town and falling in love with the rector’s daughter, Pat Lambert. One day the rector makes an unusual request.

“I want a chief fire-watcher

"But no one's going to burn it down," said Andy, looking towards the bulk of the church, "I mean-what sort of a military target is a church

"I don't suppose even Hitler wants to burn it down," he said, "but you get a raid on Sunderland or Newcastle or the docks at Darnley Port. Only needs a bomber off course, or someone in trouble with a load of incendiaries to get rid of.... Been there seven hundred years. Think about it, Andy.".

Andy sat for a moment gazing at All Saints, half daunted, half amused. A church! It seemed such an odd thing to take responsibility for in the middle of a war. It stood there, massive, so permanent.. What was it David Lambert had said? "What's the use of fighting for a country if there's no country left to come back to.

So Andy takes it on. Patricia and Archy are to be his helpers. On the night that they get their examination results the bombs start to fall. D4

The incendiaries did not fall with the dramatic roar of the high explosive bombs. They came out of the night with a sudden 'swish ... swish' like a giant scythe cutting through elephant grass. There was a bang on the tower high over their heads, and a ball of fire skidding sideways across the stonework, as if the giant with the scythe was striking a match on the tower. Like a rocket without a tail the fire bomb shot in a flaming arc into the churchyard. Now there were incendiaries all around them, each one arriving with a half-hearted 'thump' and blossoming swiftly into a rose of flame, incandescent at the heart, lurid round the edges.

Things get worse and worse.

As Andy reached the blazing steps, the bucket that Archie was using ran dry, and the jet of water spurting from the stirrup pump petered away to a useless dribble from the brass nozzle.

Archie was talking to himself.

"Ah! To hell with it!" He picked up bucket and pump and hurled them into the conflagration. They disappeared in a shower of sparks. He saw Andy come into the area lighted by the lurid glow of the fire he had been trying to control.

"Time to get the hell out of it, Andy boy. The bloody church is going to burn down.”

But something within Andy refuses to give up.

Andy did not reply. He was looking at the fire. The bomb had burnt itself out, but the steps and the shelter beneath were flaring like a bonfire. As he looked the ropes which secured steps to battlements caught fire. They burned like sparklers against the night sky. He saw the flaming steps sag as the ropes broke.

"Get another bucket," he yelled. "Chuck it down that side. We'll throw the whole lot over the edge."

It was a close call, but they were just in time. Ten minutes and three buckets of water later, the last flicker died away and it was dark in the tower, apart from the clamour of the birds and the hollow dripping of water. So at last the three of them came down from the tower, moving slowly now, round and round, all the way to the bottom and out by the great west door into the moonlight. It was quiet and still outside. The aircraft overhead had gone, the incendiary bombs in the churchyard had all burnt themselves out. Side by side they walked round the church, saying nothing, tired, emotionally drained by fear and by the tremendous demands of the last few hours.

They went into the vestry. They stared at one another by the light of the unshaded bulb. There was a moment of shocked silence, and then they burst out laughing. They looked like a trio of scarecrows, their clothing torn and burnt, their faces and hands black.

Two days later Andy receives his call-up papers for the Navy and has to say goodbye to Pat.

As evening came they sat above the little town, looking down over the roofs to the shining serpent of the river, as they had done so many times in the crowded summer.

In the middle of it all, grey in a setting of green, its gold-tipped spire still pointing to heaven, stood All Saints, serene and secure, just as it had been for half a thousand years. Andy smiled, knowing that it would not have been so but for himself and the girl beside him and Archie..He did not clearly know what he wanted to say, except that there was a debt of gratitude and a hope about the future – a future which was so blank, a tunnel into a vast mountain with exits no one knew where.

. He pointed to the church, snug in its nest of green.

“Funny to think it wouldn’t have a spire if we hadn’t fire-watched that night.”

"Yes," she said, "I'm glad we were there."

Instead of disclosing any more of the nonsense that was in his heart Andy kissed her gently.

So in the lengthening evening, hand-in-hand, they went down the steep slopes into the town.

Take care as you cross Byker Bank and head along Lime Street towards ‘Seven Stories’.

OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

"Like all stories, [this story] has no true end. It goes on and on and mingles with all the other stories in the world." David Almond –“Heaven Eyes”

Bibliography

Children’s Books set in the Lower Ouseburn Valley

The Secret by Lorna Hill

As seen from the River Tyne

Heaven Eyes by David Almond

Down the Long Stairs by Winifred Cawley

The Feast of the Serpent by Winifred Cawley

Wildcat Tower by G. Christopher Davies

Greenhorn – Richard Armstrong

Upper Ouseburn Valley, Jesmond Dene and the Parks

Marle by Aidan Chambers

Swan Feather by Lorna Hill

Joe and the Magpie by Chris Mabbot and Christine Revel (Picture Book)

Mystery in the Middle Marches by Winifred Finlay

Surrounding Suburbs – Literary Connections

Jesmond – many of the “Sadler’s Wells” and “Dancer” series by Lorna Hill

Heaton – Skellig by David Almond

High Heaton – the school attended by Sylvia Sherry

Across and Down the River

Walker/Wallsend – The Golden Gleaner by Percy F. Westerman

Wallsend – Silver Everything/Many Mansions by Winifred Cawley

Wallsend – Gran at Coalgate by Winifred Cawley

Felling – Kit’s Wilderness by David Almond

Thematically linked to a place like the Ouseburn

Steel making – Sabotage at the Forge by Richard Armstrong

Under the Luftwaffe’s Bombs – The Machine Gunners – Robert Westall

Dunkirk Summer – Philip Turner

Running (as in City Stadium) - On the run – Dick Cate

Down Underground

Whinstone Drift – Richard Armstrong

The Bonnie Pit Laddie – Frederick Grice

Gallowa – Mike Kirkup

Annerton Pit – Peter Dickinson

Down the Long Stairs – Winifred Cawley

History

Charleton’s History of Newcastle Upon Tyne (1885)